Lai e il Fiume Logone, Lai et le Fleuve Logone, Lai and the Logone River

Young girls from a village near Lai.

Vision aérienne de la rizière et des habitations des techniciens.

Aerial scene of the rice factory and the technicians' houses.

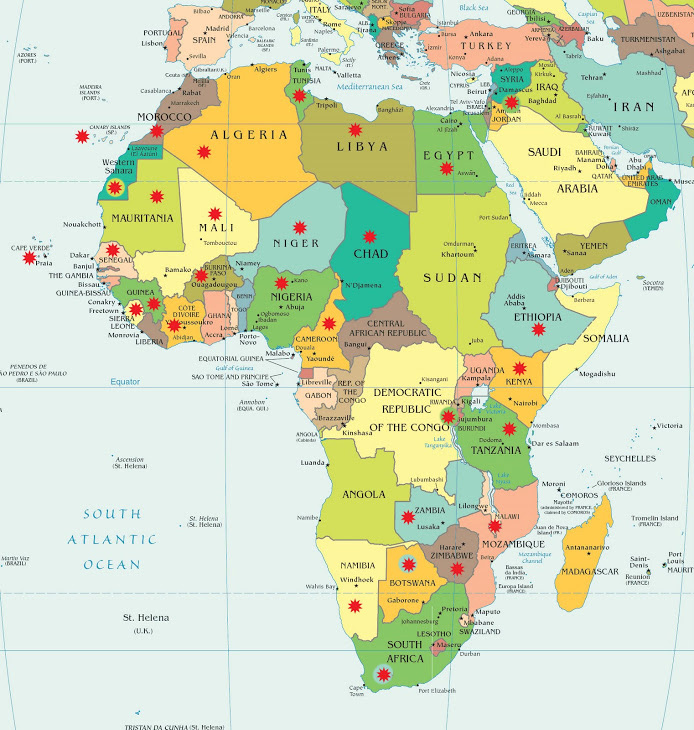

L’endroit était plutôt désolant. Mais c’était l’Afrique profonde. Sur le trajet de la capitale vers le sud, après Bongor, nous sommes rentrés dans le territoire d’une tribu dont je ne connaissais pas le nom et qui se baladaient à moitié nus. Les femmes avaient deux plateaux labiaux d’argent sur les deux lèvres. C’était la première fois que mon collègue venait en Afrique. Il habitait à Gaeta à côté de Rome. Mais il n’avait pas l’air très enthousiaste. Ça faisait des jours qu’il mangeait des fruits et des biscuits secs, fabriqués je ne sais où. En moi, je me disais: "voyons combien de temps il va résister". Le projet se révélait assez difficile d'un point de vue logistique. Heureusement j’avais remarqué que les missionnaires étaient bien équipés et possédaient un excellent garage d’entretien. Le plus sympathique était le Père Jean-Jacques, toujours en bermuda et sandales. Il était quelque peu difficile de comprendre son accent canadien, mais nous n’étions pas non plus des cracks en français et notre accent romain faisait sourire les sœurs.

La saison des pluies avait à peine débuté mais les pistes étaient déjà en mauvais état. La Land Rover restait prise dans la boue plusieurs fois par jour. Notre travail consistait à délimiter les zones propres à l’irrigation pour la culture du riz. En outre, nous devions installer, sur des points bien précis, des mires pour mesurer la hauteur de l’eau, qui aurait débordé du fleuve Logone. Les missionnaires nous avaient donné à chacun une chambre avec lavabo. Les commodités étaient à l’extérieur. Le village était dépourvu d’électricité, mais la mission catholique faisait fonctionner un groupe électrogène quelques heures par jour. La nourriture servie à la cantine était copieuse et de bonne qualité.

Deux semaines était déjà passées depuis notre arrivée à Lai. Le collègue venait en brousse pour travailler de temps en temps, il n’allait pas très bien me disait-il. Il passait le plus clair de son temps entre la mission et le village. Le soir, il ne dînait quasi jamais. Père Jean-Jacques me confia qu’il ne touchait pas non plus à la nourriture au repas de midi. Je commençais à m’inquiéter. J’ai cherché à comprendre ce qui ne tournait pas rond chez mon collègue. Celui-ci me confessa de manière candide que la cuisine de la mission le dégoûtait littéralement. J’avais plus ou moins compris qu’il s’attendait à une autre Afrique, sans doute celle des cartes postales, avec des baigneurs sous les palmiers, des savanes surpeuplées d’animaux sauvages et des hôtels de luxe avec piscine. Malheureusement, la zone de travail actuelle se trouvait dans une toute autre aire : celle de la malaria, peuplée de moustiques, loin des belles plages, pauvre, plate, dépourvue d’arbres et d’animaux sauvages, dans laquelle les gens vivaient de pêche et d’agriculture.

Après quelques jours, alors que je me trouvais loin de Lai, un homme en mobylette me donna une lettre de la part des missionnaires. Mon collègue avait été transporté d’urgence dans un hôpital éloigné avec la voiture de la mission: le docteur Tchadien de Lai lui avait diagnostiqué une appendicite aiguë. Je laissai mes occupations et courrus à la mission de Lai. Sans manger et sale de poussière et de sueur, je fis faire le plein à la Land Rover et pris la route pour Doba où devait se rendre mon collègue. Une violente averse matinale avait réduit la route en une flaque continue ; la vitesse de la course était donc limitée. La nuit tombée, j’arrivai à l’hôpital de Doba. Tout était complètement noir. J'étais très inquiet. Finalement, le gardien décida de m’amener chez le médecin russe qui gérait le complexe et je compris que mon collègue avait été envoyé à l’hôpital de Gorée où travaillait un jeune missionnaire français.

J'étais de nouveau en chemin et j’avais l’estomac qui se lamentait. Je trouvai seulement un peu de bananes à moitié noircies. La Land Rover commença à faire des caprices. Le filtre à essence était bouché. Le chauffeur était encore plus fatigué que moi. Aucun de nous ne parlait. La nuit était noire. Je décidai de prendre le volant : je me sentais plus sûr ainsi. Nous arrivâmes à Goré, le ciel était couvert de nuages menaçants. A la mission, tout le monde dormait, y compris le gardien qui fut réveillé après quelques coups de pieds donnés par le chauffeur contre la baraque en tôle. J’étais crevé. Je ne buvais pas depuis la veille. Mes lèvres étaient crevassées et ma langue sèche et gonflée. Finalement le gardien nous ouvrit. Nous comprîmes que mon collègue était arrivé le soir précédent. En effet on pouvait apercevoir le véhicule qui l’avait transporté sous les arbres dans le parking de la mission. Le gardien me dit qu’ils étaient tous entrain de dormir dans la maison de passage de la mission, y compris mon collègue. Je lui demandai de nouveau s’il avait été admis à l’hôpital mais il me dit que non et m’indiqua la maison. Il faisait encore noir et il n’y avait personne dehors. J’attendis devant la porte et j’envoyai le chauffeur chercher quelque chose à boire. Il revint avec la fameuse petite bouteille remplie de liquide noir : Coca Cola qui par chance est omniprésent. Un missionnaire entendit le remue-ménage et vint à ma rencontre.

Il m’invita à me laver le visage et les mains. Pendant ce temps, un responsable de la cuisine s’était mis aux fourneaux pour préparer du café. Assis à table, il me raconta tout à propos de l’appendicite aigu de mon collègue. Il me rassura en m’affirmant qu’il n’était absolument pas malade. Au contraire, il avait même copieusement mangé au diner du soir précédent. Je me calmais. Le café arriva avec l’alléchant parfum du pain frais. Mais la rage pris le dessus. Mon collègue nous avait tous embobinés. D’autres missionnaires arrivaient. Tout le monde me dit que le collègue allait très bien et que l’unique maladie dont il souffrait était le mal du pays. Je me levai et sortis du réfectoire. A côté de la Land Rover, je m’appuyai à un pare-boue. Je donnai un coup de poing dans la voiture pour me défouler. A Lai, ils étaient tous inquiétés par sa santé. Quel vaurien. Je sortis de la chambre en fin de matinée et comme si de rien n’était, il me dit de ne pas m’inquiéter car il était guéri et que tout allait pour le mieux. Il avait un sourire ironique. J’étais stupéfait par tant de culot. Mais au fond je me dis que c’était mieux ainsi. Je préférais travailler tout seul. Il avait avec lui tous ses effets personnels. Il me demanda s’il était possible de rentrer en Italie. J’informai Rome. Nous laissâmes la mission et prîmes la piste de retour jusqu’à Doba puis en direction de Mondou d’où il embarqua pour N’Djamena, la capitale du Tchad. Il rentrait en Italie. Il disparut de la circulation quand je reçus un coup de téléphone du bureau du chef du personnel pour me dire que je ne l'avais pas aidé dans ces moments « difficiles ».

The rainy season had just started. The roads were already pretty bad. The Land Rover got stuck at least a couple times a day. Our work consisted in delimiting the zones suitable for irrigation for the rice fields. Furthermore, we had to install, in certain areas, metric poles to measure the height of the water that would flow from the Logone River. The missionaries gave each of us a room with a sink. The bathrooms were outside. The village didn't have any electricity, but the Catholic mission turned on a generator for a few hours a day. The cafeteria food was abundant and good quality.

A couple weeks passed after our arrival in Lai. My colleague came to the field to work only at times, saying that he was not well. The rest of the time, he spent between the mission and the village. During the evening, he almost never had dinner. Father Jean-Jacques confessed that he hardly touched lunch. I began to worry. I tried to understand what was wrong and my colleague candidly told me that the food in the mission was revolting. I had a feeling that he was expecting another "Africa" like the postcards, under the palm trees or the savannahs full of wild animals or luxury hotels with a swimming pool. Unfortunately, the area where we were working was quite far from that: it was swampy, with mosquitos, far away from beaches, poor, flat, with no trees or very few wild animals, malaria; an area where the population lives on fishing and agriculture.

After a few days, while I was in the field at work away from Lai, a guy on a motor scooter brought me a letter from the missionaries. My colleague had an emergency and been brought to a far-away hospital with the help of the missionaries. A doctor in Lai had made a diagnosis of acute appendicitis. I dropped everything and ran to the Lai mission. Without eating and dirty and sweaty, I put a full tank of gasoline in the Land Rover and started, with the help of the driver, to drive to Doba where my colleague was being brought to. A violent morning rainfall had reduced the road to continuos puddles, therefore reducing the velocity. It was well after sundown that I arrived in Doba. Everything was completely dark. I became to panic. Finally, I convinced the guard to bring me to the Russian doctor who ran the complex. With the lights from the car, I was able to speak with him and he told me, through an interpreter, not to come close since he had a contagious disease. I finally came to the conclusion that my colleague had been broght to the hospital in Goré where there was a French missionay surgeon.

I stared out again. My stomach was rumbling and I found only a couple bananas. The Land Rover began giving us problems. The filter was clogged. The driver looked exhausted and I was even worse off. Neither one of us spoke. The night wsa as dark as tar. I decided to drive: I felt safer. We arrived in Gorè by sunrise: the sky was covered in black threatening clouds that didn't promise anything pleasant. In the mission, everyone was asleep, including the guard that we woke up with a few friendly kicks. I was tired and thirsty and my lips were dry. Finally the guard opened.We understood that my colleague had arrived the evening before. In fact, we could see the car that had brought him under the trees in the parking lot of the mission. I asked where he was. The guard did that he was sleeping in the guest room of the mission. It was still semi-dark and nobody was around. We waited outside the gate. I sent the driver to find something to drink.He came back with the famous bottle full of dark liquid: Coca Cola which is always around. A missionary heard the commotion and he came out. He invited me to wash up. In the meantime, a cook in the kitchen began to prepare coffee. While we sat down, he told me about my colleague's acute appendicitis. He calmed me and said that he was not at all sick; on the contrary, the evening before he had devoured his food. Well then? I tried to keep my calm. The coffee arrived together with the aroma of fresh bread. But, I was angry. My colleague had made fun of all us. The other missionaries arrived. They all told me that the colleague was fine and that the only illness he had was "Italian homesickness". In fact, he was sleeping like a baby. I got up and I went out of the dining hall. I stood next the Land Rover and leaned on the bumper. I banged on the the door of the car to let off steam. Everyone in Lai was worried about his health. What a skunk! He came out of his room later in the morning as if nothing had appened and he told me not to worry since he was fine and everything was al right. He had an ironic smile. I was shocked at his swagger. But, in the end I thought it was better. He had all his personal belongings. He asked if it was possible to return to Italy. I informed the Rome office. We left the mission and took the road to Doba and then to Moundou where he embarked on a small aircraft to N' djamena, the capital of Chad. He disappeared after a telephone call to the human resources director saying that I hadn't helped him during his "difficult" moments.